Developing the Marques and Converisions

There were two problems. One was the original workshop being too small for more than servicing and repairs. This was resolved by moving the workshop into an industrial unit in New Road, conveniently opposite Watford High Street station. This would let the ‘S’ type go into production, but the Lambretta concessionaires did not like it. There was a thinly veiled threat of terminating my dealership, eventually reduced to withdrawing the factory warranty from machines that had been tuned. No problem - I gave my own warranty and the ‘S’ type was born.

Two-tone paintwork was featured with accessories exactly as my original drawings. The first Sebring carriers were made from rod, as I could not form tube in house. I had designed an inside leg shield mounting for the spare wheel which was stronger and neater than the hook on and tensioner version available, but I only made two before a near identical mounting came from Italy, which I was happy to use. Engine alterations were modest. Ports reworked and polished, compression raised. Silencers given keyhole surgery to the first baffle, the air filter resistance reduced and the carburetor jetting changed. Finally, the side panels were sign written. It looked the business, sounded the business and saw off standard models for £225.00, which was only £10.00 more than the list price of the basic model.

Which introduces problem two: The cost of conversions. Talking to a cross section of scooter riders from all over the country (excepting a handful from wealthy families who could have been smoking around in a new sports car, but chose a scooter or perhaps both?), the acceptable price ceiling was a low one. To put it in perspective, a potential buyer of a new Vespa 150 Clubman at £160.60p might have to down size to a 125, because the deposit was £2.00 less and the 36 months repayments were £5.15p compared to £6.38p for the Clubman. Today, when a scooter sports silencer can command £250.00, it is difficult to appreciate what £1.23p a month meant in 1960? Commercially it was better to sell a new standard scooter, as the profit was eroded to supplement the cost of the conversion labour and parts. This also explains why almost every subsequent development was either modifying standard parts or adopting something existing. Producing new major parts was never an option, as the cost of development and tooling translated into an unacceptable unit price even amortized with producing the most optimistic quantity that could ever be sold.

The Lambretta was the least effected as many parts were interchangeable, including almost every gear cluster from the early Li 125 to the last GP200 - a wide choice of ratios. Vespa models did not have this versatility and tuning was also more difficult, as in comparison, the standard porting was pretty good, but - with my two-tone paint and accessories - it was well received. Development was on-going and included introducing Amal carburetion, double engine mounts and a large bore exhaust. Still prepared for street use, as the ‘on tarmac’ events were decided by target times that were easily attained.

It was a stable, almost cozy period and could have remained so without one man, Bob Wilkinson. Appointed full time secretary of the Lambretta Club in the early 1960’s, he had made most of the existing events bigger and better and then introduced us to rallies and serious competitions on the continent. Finally, and most significantly, Bob promoted full-blown track racing. Now performance and handling was everything. It was what we had been working towards for a long time, though never expecting the opportunity to unleash it.

Basic and more advanced tuning has been well documented and even the Lambretta Concessionaires accepted the inevitable and published ‘The Lambretta Manual of Tuning and Performance Conversions’, written by their Guarantee and Technical Manager, Ken Herlingshaw, but track racing required thinking out of the street user box. Previously shelved performance alterations were incorporated, as long term reliability and fuel consumption were now not an issue. Nothing was discounted and I recall replacing the flywheel with a slightly lighter weight disc, fabricating an air scoop under the cylinder cowling for cooling and ignition by battery for my own 225, just to lose the drag of the flywheel magnets and cooling fins.

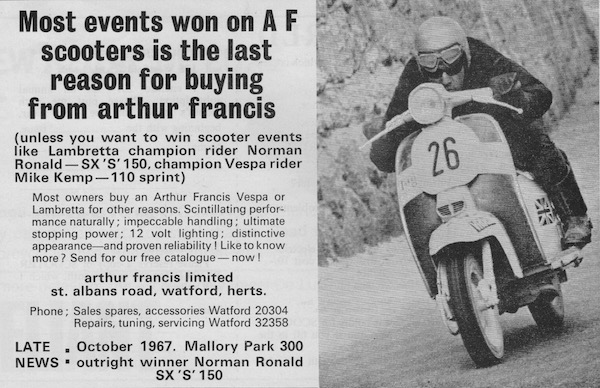

The net result was that the track ‘S’ types were successful across the board - 125, 150, 200 and unlimited - but the development input and riding skill of my staff was vital. Exciting times, but at a cost. Scooter club members were no longer able to compete on equal terms.